|

|

Monuments to a Lost Nationby Theodore J. Karamanski |

<Reprinted from Chicago History, Spring 2004>

With the bright orange glow of the setting sun at their backs, the chiefs and headmen of the Potawatomi people faced the commissioners of the United States government. Most were grave and morose as they signed the treaty ceding their homelands in the Chicago area and agreeing to removal beyond the Mississippi. The 1833 Treaty of Chicago was one of a series of agreements that terminated the native title to the American heartland and seemed to end Native American presence in the life and culture of Chicago.

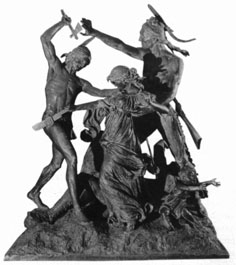

But a rediscovery of the city's native roots emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This figurative return of the native to Chicago was a symbolic encounter driven by a mixture of nostalgia, guilt, and the need of an industrial metropolis to invent a narrative that offered a common background for a community of widely diverse national origins. On the city's landscape and in its public culture, Chicagoans created statues, monuments, and illustrations durable visual representations of how they chose to commemorate the city's exiled first inhabitants.

Forward to the next page of this essay Back to Online Essays |

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |