|

American Indians at Chicago's Columbian Exposition |

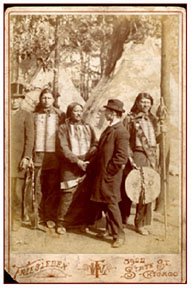

Anthropological representations of Native people provided scientific support to the racializing discourses of the day—narratives couched in terms of social evolutionism. At that time, professional anthropologists adhered strongly to the idea that all societies developed in evolutionary stages—from “savagery” through “barbarism” to “civilization.” In retrospect, we can see it was a classification scheme that was open to some criticism (The people who created the racial classification scheme had, after all, placed themselves at the top of the hierarchy. Highly suspicious, huh?). Nonetheless, anthropologists during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries believed that each “stage” was expressed in types of kinship, technology, religious beliefs, types of property, and aesthetics, and that these could be classified and compared.

Material artifacts and the results of anthropological research were laid out and presented to the public in ways that confirmed evolutionary progress and the superiority of white-skinned people. Reconstructions of Indian villages contrasted with the towering exposition buildings, demonstrating in stark terms the lack of development among Native Americans and allowing fairgoers to imagine what life must have been like when Europeans discovered Americans.

|

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |