|

Mapping Native Illinois

|

Mapping Native America poses several distinct challenges. Among the most

obvious is the fact that, before contact with Europeans, few Native groups

left written maps--or at least few such maps that survive today. From the

relatively few maps drawn by Native people shortly after they first came

into contact with Europeans, we can see an even more dramatic problem. |

|

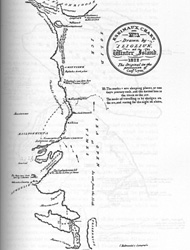

Unlike European (and American) maps, this map--drawn by an Inuit man in 1822--does not reflect a way of portraying the world using Cartesian coordinates, standardized scales of linear distance, or even cardinal directions. Instead, this map reflects the worldview of a man accustomed to using such a map to indicate traveling directions. The scale does not reflect actual mileage between two points but instead portrays the time it takes to travel between them. For example, Point A may be only a short linear distance from Point B, but the rough terrain or difficult waters between them make for a full day’s travel. The trip from Point B to Point C, on the other hand, might cover a great deal more distance, but easier traveling conditions make it possible to get there in the same amount of time. The distances between them on the Inuit map are, therefore, the same: One day of travel. The map is about human movement--by traditional means: on foot, by dog sled, or in kayaks--and it lacks the bird's eye view to which most Euro-Americans are accustomed. Instead, it appears to us as little more than a list of place names, some marks indicating resting points, and sketches of a few landmarks one would encounter on one’s journey. |

|

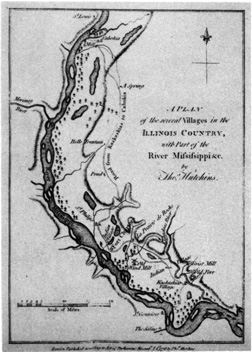

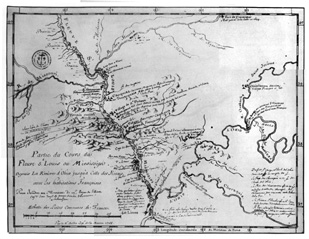

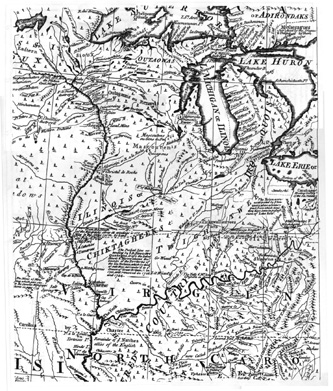

| Even if we restrict ourselves to maps drawn by Europeans, there are a number of problems to consider. The most obvious is simply that, drawn before the area was accurately surveyed, often portraying lands and indicating people that explorers heard about but never actually visited, and usually drawn (or re-drawn) after the explorers themselves were far from the scenes they describe, many maps created by early explorers are inaccurate. Distances are not drawn to scale, rivers do not flow quite where they are drawn, and lakes and villages may or may not actually be where they are said to be. Usually, though, we can compare the maps of the 17th and 18th centuries to modern ones and sort out--more or less and with varying degrees of speculation—what their makers intended to convey. But many of these maps have other problems that are more difficult to overcome. |

Chief

among these is the rather cavalier attitude many early missionaries,

explorers and government officials had

in referring to the Native groups they encountered. In many cases, the

names used to refer particular groups of people are inconsistent and

subject

to change over time. For example, a particular village in Illinois may

be referred to as consisting of "Tamaroas" on one map, "Cahokias"

or "Michigameas" in another map or report, and more generally

as "Sauvages Illinois" in a third. All of these terms may be

accurate since the village in question may have been occupied by members

of the Tamaroa, Cahokia, and Michigamea sub-tribes of the Illinois nation--either

simultaneously or one after the other--but it makes it difficult for

us

today to sort out who was living where at any given period. |

|

Another problem we often encounter on older maps and documents is a lack of specificity when it comes to tribal names. For example, the Potawatomies, Ottawas, and Ojibwes are often referred to only as gens de feu--"people of the fire" or "the fire nations". These nations are indeed closely related, but even then each possessed its own distinct identity--though no indication of this can be found on many maps. To complicate matters still further, the Mascoutens--a group whose relationship to those already mentioned is ambiguous--are also often referred to on French maps as gens de feu, probably because they lived in and among the Potawatomies at the time. There is also a tendency for mapmakers to retain the name of places and Native groups long after they passed from common usage—which complicates matters still further. |

Referring to several distinct Native groups using the same or similar names poses a problem, but we also often find many instances of a single group being called by many different names. The Mesquakies, for instance, might be referred to as "Mesquakies" (or by several different spellings of that name) on some maps, but they are far more likely to be referred to as reynards or renards--the French term for "fox", a reference to a particular clan within the Mesquakie nation though it usually refers (even today) to the entire group. Likewise, a group like the Menominees might be referred using the name they called themselves (Kayaes Matchitiwuk), by what they were called by neighboring groups (Menominee--from manomin, an Algonquin term for wild rice), by a European translation of one of these names (Folles Avoines) or by one of several variations of any of these. |

|

|

|

|

Another difficulty in mapping Native America is that most of the groups living in or near the region that would become Illinois were extremely mobile. Many Sauks, for example, lived in Saukenuk--a large village at the confluence of the Rock and Mississippi rivers—during the summer months then dispersed during the fall and winter into smaller hunting camps to the west. Some agricultural villages—like Saukenuk or the Grand Village of the Illinois--were more or less permanent affairs because of the fertile land and rich resources surrounding them. Others, however were less so--occupied for a few years or even a generation before being abandoned as its inhabitants selected a new village site. The maps above, for instance, show no fewer than five Shawnee villages labelled "Chillicothe", five called "Piqua", and several others with multiple locations--a result of frequent moves within the period the maps attempt to portray. For people whose lives depended on seasonal and non-seasonal movements, static maps often leave much to be desired.

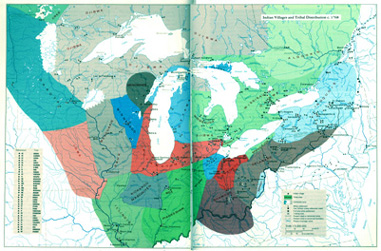

This map (below), perhaps more than any other, illustrates a conspicuous limitation inherent in even the best of maps portraying Native America. Helen Tanner's 1986 Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History--the product of years of painstaking research by one of the most highly regarded experts in the field--is generally considered by scholars to be the definitive work of its kind. |

|

Clearly, its geography is accurate: waterways and landforms are located precisely where they ought to be. Tanner and her associates also combed numerous archives and checked countless sources (some contemporary, some historical or archival, others archeological) to accurately identify, name and describe individual villages and place them exactly where they were actually located. Yet even it is limited in its presentation. |

On the map shown here, for instance, the areas most closely associated with each group are indicated by shading them using different colors. The problem, however, is that this implies strict and recognized boundaries--like those separating one state from another—that simply never existed between Native groups. Tribal boundaries (social, political, and geographical) were never fixed or static. Individual villages might contain members of many different groups, several unrelated groups might all use and claim ownership of the same general area, and they may allow still other groups to live on and share the resources of lands they consider their own (often referred to as letting one's allies "sit down" upon the land). Certainly, one would never find a line distinctly separating Sauk territory from that of the Winnebagoes in the same way one can find a border between Western nation-states like France and Germany or even between American states such as Illinois and Indiana. |

On

this site we have attempted to illustrate the difficulties of mapping

Native America--and to at least partially overcome

them using various techniques

and technological methods. Our tribal pages, for example, contain maps

indicating movement of Native groups over time, thus reflecting the dynamic

historical processes in which these groups played a part. The link belowwill

take you to one of our interactive mapping tools which may help indicate

the degree to which the "territories" of Native groups overlapped

with one another--forcing a high degree of intense interaction between

groups most of us are accustomed to thinking about as discrete and separate

units. This interaction could range from coexistence, blurring tribal

distinctions, blending and merging to hostile competition, international

conflict, and

war. In any event, though our own maps are limited as well (and subject

to criticism), taken together with the maps discussed throughout this

essay, we hope they will help show the complexities inherent in mapping

Native

Illinois and elicit further thought and discussion. |

<Link to Yiqi's Overlay Map>

If

you have questions or comments about this essay, let us know. Send

an email to: AIIOP@?????.uiuc.edu. Please include the

subject heading "Mapping

Illinois". |

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)