|

"It Grew Out of the Ground":Lorado Taft's "Black Hawk"

by Michael Sherfy

|

This article is adapted from a paper presented by the author at the fourth annual CIC conference on American Indian Studies, held at the Newberry Library, Chicago, IL in April 2003.

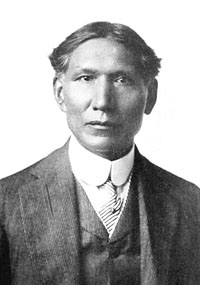

At right is Black Hawk…sort of. The above portrait, drawn from life by George Catlin while Black Hawk was being held prisoner at St. Louis, is probably a good deal closer to the "real thing". What the picture at right actually represents is sculptor Lorado Taft’s attempt at "capturing the spirit of the Indian," which took the form of a colossal statue overlooking the Rock River near Oregon, Illinois. Taft was a native Illinoisan—born in Elmwood on April 29, 1860, educated in Champaign (indeed, the University of Illinois, which Taft entered at the age of 15 while it was still called the Illinois Industrial University, was the first educational institution he attended—earning his B.A. in 1879 and one of the school’s first graduate degrees a year later), and a longtime resident of Chicago. His works are known the world over, but they are concentrated here in his own state; over twenty are currently displayed within Illinois’s borders. In terms of magnitude and sheer visibility, none compare to his "Black Hawk". |

|

The origins and production of this monumental work warrant some explanation. Since the mid-1880s, it had been the custom for Lorado Taft to take leave of his studio and, along with his family and a collection of his artistic colleagues (such as the writer, Hamlin Garland; the painters, Ralph Clarkson and Charles Frances Browne; and the architects, Samuel and Irving Pond), escape from the heat and noise of the Chicago summer by spending several weeks camping in the woods. Their favored location was Bass Lake, Indiana, but the appearance of malaria in the vicinity in the mid-1890s convinced them that a new site was necessary for their little camp. Wallace Heckman, a law professor at the University of Chicago, offered Taft’s circle of friends the use of part of his Rock River estate, "Ganymede," to create a summer artist colony. They accepted and, in 1898, camped out in tents on the bluff above the river. They took to the place, arranged a long-term lease of a few of Heckman’s acres, and built a kitchen and several cabins. With his own hands, Lorado Taft built a cabin and an open-air studio which he used extensively—transferring several works-in-progress from his Chicago studios to Oregon each Spring. |

Taft founded the Eagle’s Nest Artist Colony—named for a Margaret Fuller poem composed on the site—an inspirational place to work. For several years he pondered—unsuccessfully—how he might channel his creative energies into a work that adequately captured the essence of the place. Taft decided that a more exotic than his usual fare was appropriate. He envisioned that an immense Indian overlooking the Rock River would serve both to honor Illinois history and stand as a tribute to the "savage yet noble" qualities of the Native American race.

|

|

His subject now determined—perhaps as much by the romanticized notions of his colleagues at Eagle’s Nest as by any firsthand research into the region’s history or into the actual cultures of the area’s earlier inhabitants—Taft had to devise a way to bring his idea to fruition. Erecting such a colossal statue as he had in mind would have been difficult under the best of conditions. Erecting it at a remote location like Eagle’s Nest seemed almost impossible. The artist considered the logistics of the task for a number of years before he finally arrived at a plan. The solution came to him while Taft casually observed workmen as they installed several chimneys atop Chicago’s Art Institute in 1907. Taft decided that his "Indian" could be made of concrete, poured into a plaster mold created on site and reinforced by steel bars. Such a thing had not been attempted by any sculptor before but, after consulting with individuals with more experience working with concrete, Taft thought it might work. So, in the summer of 1910, the entire camp pitched in to help turn Taft’s six-foot scale model into a full-sized statue. By mounting a scaffold bearing a plywood silhouette upon a wagon, they searched for the most striking and effective location on the bluff. The Portland Cement Company agreed to furnish material in exchange for the right to use the finished product in its advertising. John Prashum, an assistant in Taft’s Midway Studios, was placed in charge of creating the huge mold for the concrete. |

Prashum

created a vast framework of lath, chicken wire, and burlap seven times

the size of Taft’s working model. Hollow cast plaster sections were

then hoisted and fastened into place on a wooden frame which was reinforced

to withstand the pressure of the concrete. The gigantic head (modeled not

on Black Hawk or any other Native person but on Lorado Taft’s brother-in-law)

was cast full size on the ground near Taft’s cabin where it could be more

carefully crafted. Taft’s daughter described the head as "an astonishing

thing, reaching to the eaves of the house. Many of the young people and

children at Eagles nest helped ‘butter’ it, that is, spread the clay over

the framework of wood and wire." When complete, the concrete head

was lifted into position and placed above a three-foot wide hollow tube

that

would run through the center of the statue to allow the concrete to expand

and contract without cracking. |

Before cold weather set in, Taft and Prashun cast an eighteen-foot square concrete base upon which they erected scaffolding and prepared the mold. By November, 1910 all was finally ready. The cavernous interior of the mold received a spray of paraffin and clay water to prevent it from sticking. Over two tons of steel rods were built into the interior to support the statue’s head and reinforce the concrete. The weather did not cooperate. A storm blew down the scaffolding and delayed the project further into the winter. Water for casting had to be pumped up from the river below and Prashun had to improvise a heating system to prevent it from freezing. The entire (rebuilt) scaffold was wrapped in a huge canvas to protect it and the workers from cold and wind. |

Once the casting began, it had to continue without interruption until complete or the entire effort would fail. On December 20th, the heated water was ready, the concrete and sand waiting, and they finally began casting. At times, the temperature, high on the exposed bluff, dropped to two below zero. Two teams of fourteen men each worked around the clock for ten days and nights. At 2:45 p.m. on December 30th, the mold’s cavernous hollow was filled to the top. There was nothing left to do but wait. It was not until Spring that Taft, Prashun and their associates were certain that the concrete would set properly. Over 6,500 gallons of water, 412 barrels of Portland Cement, two tons of steel rods, 200 yards of burlap, and ten tons of plaster went into Taft’s "Indian." Completed it stood nearly 43-feet high above its base and weighs over 268 tons. It was visible from a railroad bridge nearly two miles upriver. A feat of engineering as well as art, the details of the statue’s construction were outlined in a 1911 article in Popular Mechanics. |

Though

the artist paid for much of the cost of producing this massive work

himself, local businesses and several of the area’s

most prominent citizen’s contributed as well. These patrons, as well as

the townsfolk of Oregon and wealthy Rock River landowners like Governor

Frank Lowden (whose 5,000 acre estate, "Sinnissippi"—now a state

park—lay immediately adjacent to Wallace Heckman’s property and the Eagle’s

Nest colony) would see the statue virtually every day and they were not

universally pleased with Taft’s original vision. |

Many wanted Taft’s monumental "Indian," a tribute to the noble and virtuous qualities of romanticized Native Americans in general, to have a more explicit local connection. Black Hawk provided the obvious solution. Black Hawk (1767-1838) was a Sauk war-leader who, in defiance of federal order and several treaties that he deemed invalid, returned to his home in Illinois in 1832 and set off a four-month armed conflict with the United States that eventually involved over 6,500 American soldiers and marked the last armed Algonquian resistance to American expansion east of the Mississippi. After his defeat and capture, Black Hawk became a national celebrity during a government-sanctioned tour of the East in 1833—a celebrity that became permanent with the dictation and publication of his autobiography the following year. Oregon, the town nearest the statue, is located in Stillman Valley where the first "battle" of the campaign against Black Hawk had been fought. In the eighty or so years between his expulsion from Illinois (which served also as the catalyst for the expulsion of all organized Native communities from the state) the old Sauk warrior, safely absent and long dead, had become something of a regional hero. Unofficially re-naming the statue for Black Hawk was an obvious way to satisfy everyone. In his resistance to American expansion, he embodied the "noble and unconquered" spirit of the Indian that Taft sought to represent. In being defeated, Black Hawk fit nicely into the mold of the "Vanishing Native" that predominated in the popular conception of American history at the time. Perhaps most importantly, his ties to Illinois in general and to the Rock River in particular were well-established. (If local tradition and place names are any indication, Black Hawk spent the bulk of his time sitting on large rocks and gazing out over the Rock River. From Black Hawk’s Watch Tower at Rock Island to Indian Rock and Indian Head Rock thirty or forty miles upriver, to the bluff at Eagle’s Nest and Squaw Rock still further up the river, if there is a place to stand along the Rock River and a scenic view to admire, some guidebook or area resident will assure you that Black Hawk is said to have enjoyed it). |

In naming the statue for Black Hawk, however, the central meaning of the work shifted. In an obvious way, Taft’s romantic portrayal of a generalized "Indian" became a tribute to Black Hawk alone—a single individual rather than a representative of a race. Less obviously, though perhaps more significant, in acquiring a new name, the statue ceased to be connected to a people or a person at all and came instead to be seen as an embodiment of place—a celebration of the Rock River country. |

That Taft’s statue was not really intended as a tribute for Native Americans was apparent, at least to some observers, almost immediately upon its completion. At its official dedication on July 1, 1911—an event that was later described as "an exclusive assembly of 500 sculptors, painters, authors, poets, and millionaires,"—two of the specially-invited guests even called those present out on that particular point. The ceremony opened with a fairly long oration by Edgar A. Bancroft, <credential>. While it is not necessary to reproduce his speech in detail, a few quotations can give you an idea of its general tone. Bancroft opened by stating that "All primitive peoples are of absorbing interest, because of the light they shed on the origin of the human species…" Later: "They [the Europeans] found the American Indian, a true child of nature…a simple race that roamed the woods and the prairies, camping where the night found them, living freely…Like the wild fowl or the bison, they journeyed and lodged in ever-changing groups, supplying their daily needs wherever they were and always at home, no mater how widely they fared….Though he sometimes had so-called villages, and even federations, these were uncertain, often remote and transitory." Of Black Hawk’s defeat by the United States, Bancroft said: "We can read a tragedy there, but it is a tragedy that does not depress, that does not appeal to gain sympathies; it is a hopeless fight, but not a surrender; it is a lost cause but not a lost leader." |

|

Dr. Charles Eastman was called upon to deliver the next oration. The Dakota physician began his remarks by saying that Bancroft had "stolen his speech" (an intriguing choice of words that his audience probably assumed meant that Bancroft had made the points that Eastman had intended to make, but could just as easily be interpreted to mean that his remarks had left the good doctor speechless). Speaking extemporaneously, Eastman proceeded to undermine many of the assumptions about Native cultures that Bancroft had just described. He pointed out that, though people like Black Hawk had lacked books, they were far from "untutored savages." Nor were Indians the "heathens" that Bancroft described, since they "never knew a hell or had a devil in [them] until the missionaries came here." Eastman critiqued also the "civilization" that settlers brought to the frontier: "We loved our homes, our villages and our prairies," Eastman explained, "but we had no business here. We had no civilization. You had plenty of it my brothers, and the more you have, the more you’re afraid of your brother, and the more strong doors you have, the more policemen to protect you." |

Like Eastman, Laura Cornelius, the daughter of an Oneida chief, was both appreciated by the audience but somewhat critical of the day’s proceedings. She pointed out that, though Taft’s statue was ostensibly intended as a tribute to native Americans, none were present. "No eagle plumes are before my eyes as I look among you." she began. The race is not here to-day. The race is not here…" She continued by saying that while she felt privileged to represent the American Indian on this occasion, she felt "profound regret" that "a Red Jacket, a Dehoadilum, or an Oshkanundutah [was] not on hand to immortalize the occasion with a more fitting speech." Ms. Cornelius had a good point. While Lorado Taft and his Eagle’s Nest circle had invited no shortage of "sculptors, painters, authors, poets, and millionaires," no Indians had been invited except for Charles Eastman and Laura Cornelius—both well-regarded intellectuals. Black Hawk’s living relatives (by then removed to Oklahoma and Kansas) had not been invited. Nor had the affiliated Mesquakies living not so far away in Tama, Iowa or any other Native group that had been associated with the area. For a tribute, Taft’s "Indian" was a well-kept secret from most of its honorees. So if Taft’s statue does not honor Native Americans in general to quite the degree to which the artist intended, it at least honors Black Hawk as an individual…Well—sort of. The statue bears the Sauk war-leader’s famous name—but only unofficially. Its actual title is simply "The Indian." It doesn’t look like Black Hawk, was modeled after a White man, and does not even portray an individual in typical Sauk dress. Further, the statue sits nearly sixty miles up the Rock River from Saukenuk, the village at which Black Hawk lived for most of his life. During Black Hawk’s lifetime, the area around Oregon was most closely associated with the Winnebagoes and Potawatomies—and before them the Illinois, not the Sauks. Black Hawk may have known it—hunted there, visited kin in the area, or passed through it on his way to visit British friends in Canada—but the country captured by Taft’s "Indian’s" admiring gaze never really belonged to him. So…if Taft’s "Indian" doesn’t really honor Indians and doesn’t really honor Black Hawk, what does that 43’ colossus do? I would argue that it serves the symbolic function of honoring the place in which it was constructed. While evidence to support such an argument is not always explicit, it is by no means difficult to find. For example, though Black Hawk left a substantial autobiography that had much to say about a wide range of topics—from land dispossession, to cultural differences, to slavery—only one quotation from the Sauk warrior was cited at the dedication--and that not from his book but from a Fourth of July toast he delivered at Fort Madison, Iowa in 1837. It read: |

|

A few summers ago I was fighting against you. I did wrong,

perhaps, but that is past--it is buried--let it be forgotten. Rock River

was a beautiful country. I liked my towns, my corn-fields, and the home

of my people. I fought for it--it is now yours--keep it as we did. |

| These remarks--an admission of defeat and wrongdoing by a seventy year-old man, followed by an admonishment to those who defeated him to look after the country from which he had been driven—are the closest thing to a direct connection to Black Hawk that folk saw that day in 1911. They remain so even today; On my last visit to the site last summer, these remained the only words spoken by Black Hawk available to visitors at the site's welcome center or in its informational literature. Other than this toast and a biographical paragraph or two, the historical Black Hawk is simply not present. As recently as yesterday, this quote was the only one posted on the Northern Illinois University webpage referring to the statue. (http://www3.niu.edu/historicalbuildings/leaders_hawk.html) |

Tellingly,

though, the constructed Black Hawk so magnificently represented by

Taft's "Indian" is ubiquitous not only at

the site but throughout the area. His name is everywhere: Credit Unions,

Schools and Colleges, Boats,

Boy Scout Troops, Local Clubs, and even an open-pit steak restaurant

take Black Hawk's name and likeness as their own. |

Many institutions including the state highway signs that mark the Black Hawk Trail, use Taft's "Indian" rather than an actual portrayal of Black Hawk as their insignia. Even the local boy scout camp—whose campers, at least in theory, actually do learn something about the Native groups who had lived in the region—awards medals bearing the statue's likeness rather than the historical person's. Whether he actually lived there or not, and whether or not the imagery looks as he did, one hundred and seventy-odd years after his removal from the state, there can be no doubt that the Rock River Valley today is "Black Hawk's country". |

My dissertation, into which several elements of this paper will eventually be incorporated, will discuss in greater detail the mechanics through which the living Black Hawk became recorded in the historical record then was subsequently re-shaped and re-constructed into much less recognizable forms. That Americans, whose history is rich but comparatively recent, feel compelled—even driven—to appropriate Native American history and imagery to tie themselves more directly and deeply to the land they now occupy is by no means an original observation, but it remains a fascinating one…and few examples illustrate this process more clearly than does Black Hawk.

Lorado Taft said of his statue, "It grew out of the ground." That may be true…but if it did, it was only because nostalgic people craving a deeper and richer history needed it and planted it there. |

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |