-smaller.JPG) |

The Story of the Rocks

|

THERE

was a time—hundreds of million of years ago—when

the flat top of Starved Rock was but a spot in the sandy bottom

of an ocean—an ocean that covered most of the Middle West!

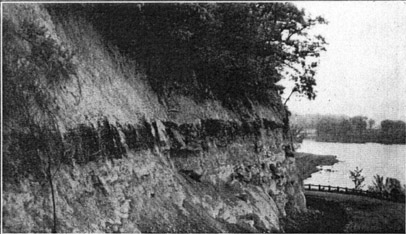

The Exposed Coal

Seam at Buffalo Rock

|

The waters of that ocean had gradually

invaded most of the land, creeping in stealthily its some

places and in others with the force and power of a mighty

torrent. The high Ozark Mountains of Missouri kept their

heads above the water,, but few indeed were the other spots

left unsubmerged in this vast area. This ocean deposited

a layer of clean white sand now called Saint Peter Sandstone.

Ages later the waters receded, then returned and once again

retreated in their never-ending battle with the land

For

a time—perhaps a hundred thousand

years or more—plants took root and flourished in the

soft sands. The climate was tropical, warm, and sultry

all the year round. Great fern-like trees sprang up; mosses

as high as a man’s waist grew in their shade. But

this was not for long. The seas returned, depositing their

layer, of sand over this luxuriant vegetation, forcing

it into compact lavers, from a foot tot eighteen inches

thick. As more sand settled ins these layers of vegetation

its the many years that followed, they turned into coal. |

-1-smaller.JPG)

Rock Layers that

Tell... |

The pre-historic ocean that deposited

the sand entered the valley many times. Some idea of the

number of times it covered the site of Starved lock can

be gained by counting the various strata of the rock and

its surrounding cliffs.

Only

a million years ago—a comparatively

recent period as geologists measure time—the earth

grew steadily colder. This change did not take place abruptly,

but over a period of many thousand years. It began to snow

during the winters. Each year it snowed more, and the snow

stayed longer. Then came the first great glacier, pressing

clown from the frozen north, a mountain of ice that extended

as far as the eye could see—had there been men or

animals to see it. After several thousand years this glacier

began to melt, and its icy waters loured down the valley

of the Illinois River.

Several such glaciers moved down from

the north, covering Starved Rock with sheets of ice several

hundred feet thick. When they melted their waters flowed

down the valley, cutting through the softer parts of the

sandstone and leaving the harder portions to form the fantastic

shapes we now see in the park. |

Even the canyons were cut by

the rush of glacial waters as they tossed and churned on

their way to the Gulf of Mexico. Each spring the waters

spread out over the plains, then cut their way back to

the river. Heavy rains and thawing winter snows also contributed

to the torrents that washed away the rocks. Waterfalls

were formed where hard, cemented layers of stone gave way

to soft sand that was easily washed away. The process has

not ceased. The little rivulets that now flow in the canyons

imperceptibly but constantly wear away the rock over which

they flow.

The many caves in the bluffs were formed

by streams of water that forced their way under the rock,

undermining the cliffs. The over-hanging rocks fell when

their supports had been washed away, leaving caves that

provided shelters for the earliest inhabitants of the valley.

Most of these caves are small, but one, Council Cave, is

large enough to permit a thousand persons to stand beneath

its sheltering roof.

The ancestor of the Illinois River that carried

the torrents of glacial waters was more than a mile wide

and extended from bluff to bluff. At one time it covered

the broad flood-plain on the northern shore; now it is

a small stream, occupying only a small portion of its former

bed. Once, in its early days, it was strong enough to send

its eddies between the rock and the bluff, carving out

tine valleys that separate Starved Rock from the bluffs. |

-2-smaller.JPG)

...the Story of the

Rocks.

|

The trees and flowers that thrive in

tire park are all native to Illinois. The oldest trees

in the park are white pines, reminders of a day when once

these towering giants were lords of the soil. Oaks, maples,

elms, and many other species now predominate where once

the pines were most common. Bushes of all kind, known in

Illinois thrive ]it the moist sandy earth. Ferns with great

broad fronds cling to rocky ledges where even a bird could

not rest. The forest floor is covered with wild flowers

of all the varied hues of the rainbow. The delicately shaded

columbine with its red and white flowers may he seen in

any canyon and along any of tit, wooded paths. The foxglove,

too, grows in profusion. Protected from drought by the

porous sandstone which ever yields it, moisture to plants,

these and a thousand other flowers bloom at Starved Rock

every year.

Where now the squirrel scampers to bury

its food, once roamed more ferocious animals in search

of their prey. Wildcats, bear, and wolves had their hiding

places in these words. Buffaloes and deer were the first

citizens of this state of nature. Along the waterfront

and in the swamps were the mounds of muskrats and the darns

of beavers. These, however, are long gone. The Indians

hunted them and reduced their numbers and the steady push

of the first settlers drove them to the farther west. Only

those animals titan can live in friendship with man have

survived.

Frenchmen visiting the Illinois valley

in tire seventeenth century mentioned the brilliantly colored paroquets that

lived lure at that time. Today these are no longer seen,

but the little wren is still merry with song and the cardinal

is a spot of red in the tree. The red-winged blackbird,

the scarlet tanager, the canary, and the blue-jay lend

their colors to the bird-life in which the park abounds. |

Back

to Starved Rock:History and Romance in the Heart of the West

Page

|