|

|

Monuments to a Lost Nationby Theodore J. Karamanski |

<Reprinted from Chicago History, Spring 2004>

McCutcheon's cartoon first appeared at a time when there was a growing interest in the Native American history of the heartland. Major archaeological studies explored effigy and burial mounds throughout the region. Even within the Chicago metropolitan area, amateur diggers explored the city's prehistoric past to the dismay of professional archeologists because of the amount of site disturbance. Some collectors simply used the pots and points they discovered as decorations. One North Side tavern owner decorated his watering hole with thousands of prehistoric pieces. One of the most assiduous of these amateurs was Karl (also known as Charles) A. Dilg, a journalist who devoted severa decades to collecting Indian artifacts and studying sites. in the Chicago area. Dilg had grander aspirations and assembled his findings into a massive study he titled Archaic Chicago. Another German American, Albert F Scharf, amassed a huge artifact collection of his own and also aspired to write the definitive work on Chicago's Indian past. Dilg disparaged Scharf as "a mere relic hunter," and claimed, "what little knowledge he has, and God knows it is very limited, he received at our hands."

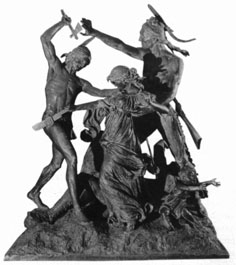

"Injun Summer" proved extremely popular with Midwesterners. Newspapers across the country reprinted it, and it appeared annually in the Chicago Tribune from 1912 to 1992 as a cherished and anticipated seasonal ritual. Unlike the statue The Alarm, which accurately depicted Ottawa Indians and was based on personal memory, "Injun Summer" displayed little connection to the genuine Native Americans of the Midwest. McCutcheon dressed the ghostly Indians in the long feathered headdresses of the Plains Indians; the lodges that appear in the harvest moon are not the bark wigwams of the Great Lakes Indians but the buffalo hide tepees of the far west. More importantly, the Native Americans depicted in "Injun Summer" are identified as a furtive part of the landscape, cloaked from normal view by the light of day and hiding in the shadows, awaiting the harvest moon to make their appearance. The Indian figures rise up from the smoke of the burning leaves, appearing to emerge from the very ground. This close identification of the Indian with nature had long been part of the European American image of Native Americans, from jean Rousseau to James Fennimore Cooper to Frederick Jackson Turner. "The Indian is a true child of the forest and desert," Francis Parkman wrote. "His unruly pride and untamed freedom are in harmony with the lonely mountains, cataracts, and rivers among which he dwells; and primitive America, with her savage scenery and savage men, opens to the imagination a boundless world, unmatched in wild sublimity." The turn of the century Midwest, however, had lost not only most of its Indians but also its "wild sublimity." The sense of loss, perhaps even guilt that emerges from the cartoon Indians may well be the emerging nostalgia of an urban people for their own loss of the rural American heartland. From McCutcheon's day to the present, virtually every train arriving in Chicago carried a migrant from the countryside to the city. No sooner had the generation that had dispossessed the Potawatomi, Ottawa, and Illinois died off than many of their descendents themselves were dislodged from the land by mechanization and market changes, a process that continues to this day. It is ironic that the Chicago Tribune, the voice of the urban business establishment that made such changes inevitable, would create the image that for thousands of city dwellers symbolized their loss of a landed heritage. Click here to view McCutcheon's "Injun Summer" and make your own decisions about it.

Forward to the next page of this essay Back to the previous page Back to Online Essays |

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |