|

|

Monuments to a Lost Nationby Theodore J. Karamanski |

<Reprinted from Chicago History, Spring 2004>

Not surprisingly, two of the most important artistic additions to Chicago's public space during the 1920s were Native American figures. As part of Daniel Burnham's 1909 plan for Chicago, a formal entrance from the Loop commercial district to Grant Park would be ornamented with two large sculptures. The commission for the project went to Yugoslavian artist Ivan Mestrovic.

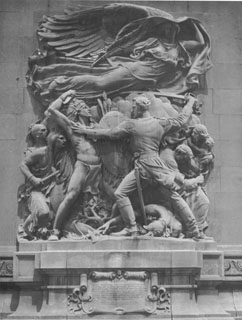

The second great addition to the city's public space in the 1920s was architect Edward Bennett's Michigan Avenue Bridge. Also part of the Burnham Plan, the bridge sat amid the most impressive architecture of 1920s Chicago: the Wrigley Building, the Chicago Tribune's gothic tower, the Jewelers' Building, and the London Guaranteed Insurance Building. The location was the site of the original Fort Dearborn, so Bennett choose a series of bas reliefs depicting the early history of Chicago to decorate the massive Indiana limestone pylons of the bridge.

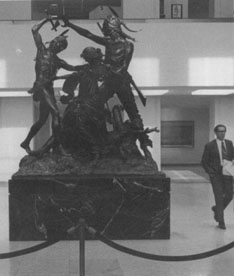

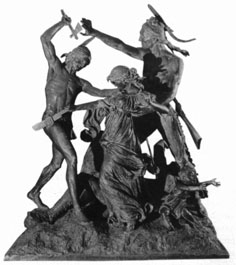

With the closing of the 1920s, Chicago muted its public dialogue with its American Indian roots. The statues "The Alarm", "The Signal of Peace", and the "Fort Dearborn Massacre" all moved to new locations. The "Fort Dearborn Massacre" suffered from vandalism after the elite Prairie Avenue neighborhood waned in status and factories and warehouses replaced its mansions. In 1931, the Chicago Historical Society (CHS), to which George Pullman had left the sculpture upon his death, moved the figures to its North Side museum, separating the monument from its base. Rohl Smith's bronze group became the dominant image of pioneer Chicago for schoolchildren visiting the museum. In the 1950s and 1960s, when young television viewers mimicked Davy Crockett by sporting mock raccoon skin hats and brandishing cap guns, the statue was proudly and prominently displayed. The shift in social tenor triggered by the Civil Rights Movement and the Vietnam War brought new sensitivities to the fore. In 1972, the Chicago Historical Society added a subtitle to the statue, "The Potawatomi Rescue", in an attempt to mute a groundswell of criticism of the bronze's dated imagery. The relabeling did not prevent a protest rally at CHS in 1973 by dozens of American Indians. The protestors lamented the overall depiction of Native Americans in the Historical Society's exhibitions, and they singled out the "Massacre" for its negative view. While Rohl Smith had used survivors of' Wounded Knee to accurately depict the American Indian, eighty years later the Native Americans invoked the memory of the event to attack the iconography of the monument: "Why don't they show our side of it?" complained one protestor, "Wounded Knee was a massacre too." Despite such protests, the monument remained eon display for more than a decade but became an increasing source of embarrassment for CHS.

CHS gave the monument to the city of Chicago, which returned it to Pullman's old Prairie Avenue neighborhood. A single half block of elegant old homes remained of what was once the most elite area in the Midwest, a historic district island in a declining industrial belt. Pullman's old mansion had long since been replaced with a railroad office building, so the city placed the statue group approximately a half block away from its original location. For nearly a decade, the monument sat forgotten in a small, unimproved green space. In 1997, it became an embarrassment once more, as the city sought a site to honor the First Lady of the United States. The unnamed green space occupied by the Massacre was landscaped in preparation for its dedication as the Hillary Clinton Women's Park. Not only was the statue considered racist, but even more embarrassing to those planning a women's park, it depicted a helpless woman in distress. The city packed up the statue; it currently sits shrouded in a blue plastic tarp at a city storage facility.

Forward to the next page of this essay Back to the previous page Back to Online Essays |

| |

Department

of Anthropology |

copyright © 2002

University of Illinois, All rights reserved. |